The Bond movies have often strayed a long way from their source novels (and short stories), but Ian Fleming's original material continues to creep into the films in sometimes surprising ways. With bits of Octopussy infiltrating Spectre, we break down what comes from where.

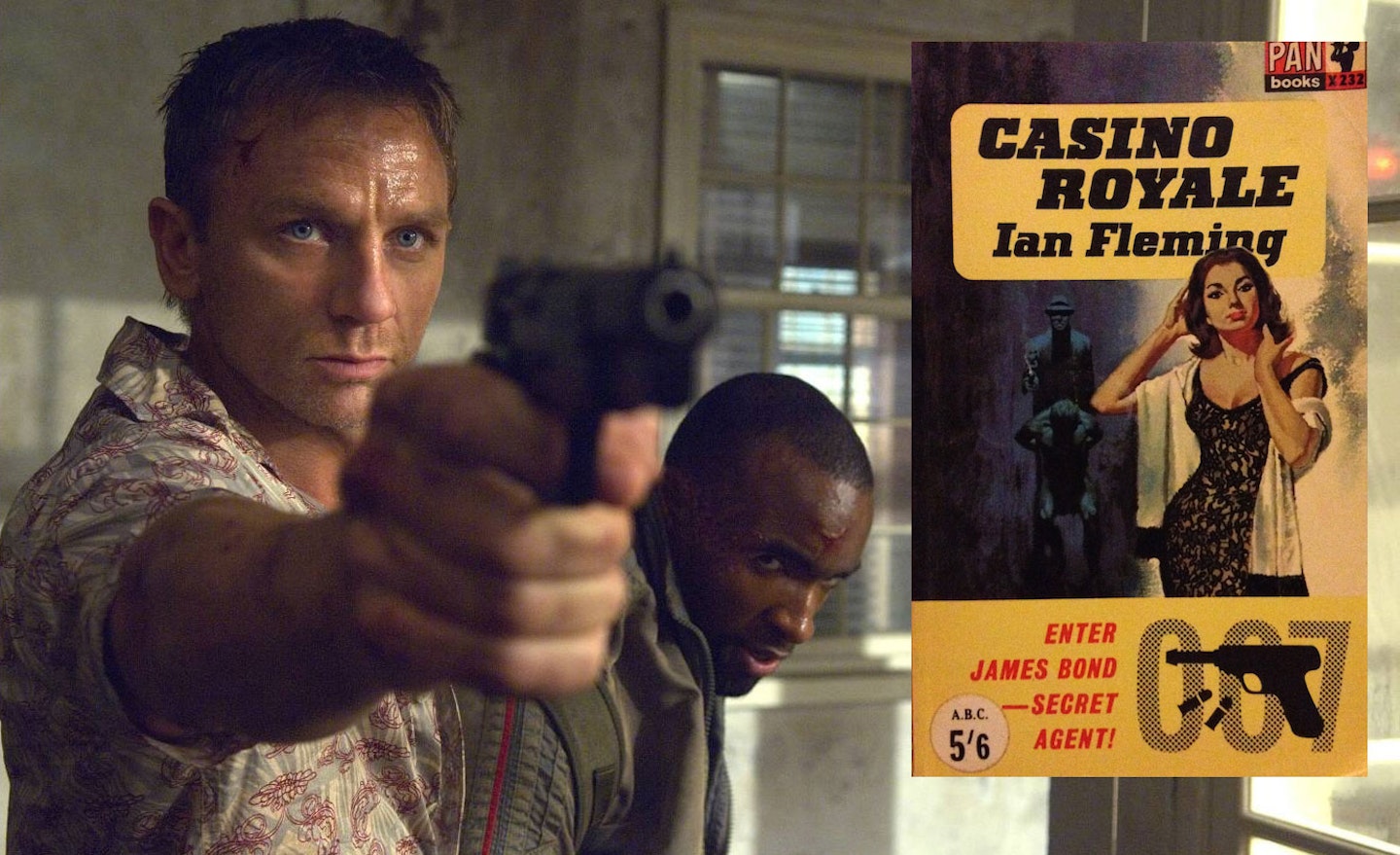

Casino Royale (1953)

Filmed in 2006

Fleming's first Bond novel - with its rights finally available again having been tied up since the 1960s spoof - formed the basis of the official film series' reboot at the start of Daniel Craig's tenure. In many ways the film is the most faithful Fleming adaptation for decades, but there are plenty of differences too, most of which come with the update. The broad plot of Le Chiffre losing the money of his powerful clients and trying to win it back at the casino while Bond attempts to mess up his plan is straight from Fleming. In the book, however, Le Chiffre is in hock to SMERSH not Quantum, and the card game is Baccarat not Poker. The torture scene with the bottomless wicker chair is from the book (with the slight change that Fleming's carpet beater becomes a knotted rope), although Fleming is more interested in the psychological toll while the film concentrates more on the physical. The dry martini recipe and naming it The Vesper is Fleming's, but the film adds the action beats of the parkour chase, the airport sequence and the collapsing Venice house: Vesper commits suicide in the book, but not by locking herself in a cage in a sinking building. The film doesn't use Fleming's big scene with the camera bombers, but it does use Bond's devastating line "The bitch is dead" - although he means it slightly differently. Bond also gets a philosophical speech in the book which ended up in Quantum Of Solace, but was given to Mathis.

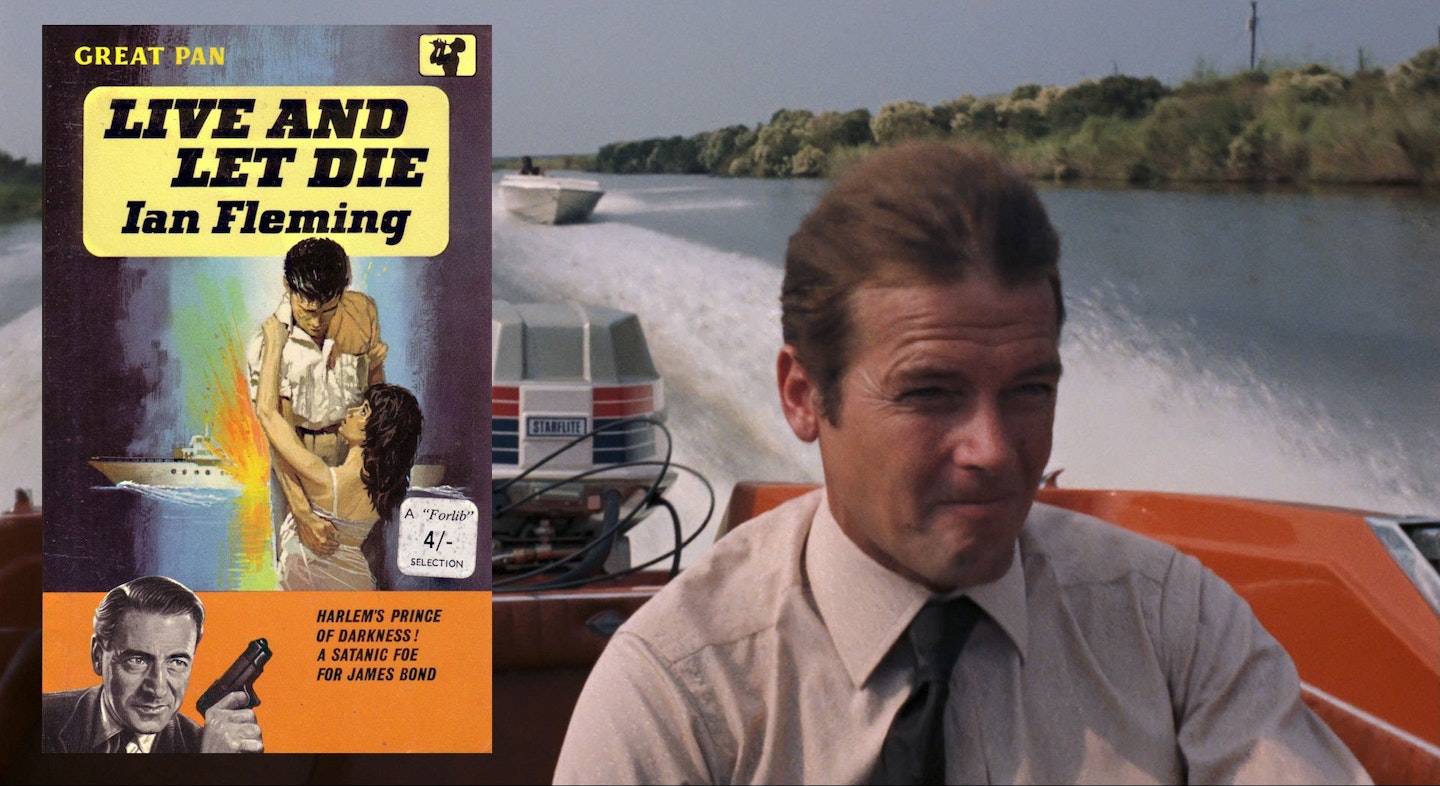

Live And Let Die (1954)

Filmed in 1973

The second novel becomes the eighth film, and Roger Moore's first as Bond. The characters and the "vibe" of the film are more-or-less Fleming's, but the story's pretty far off. In the book, Mr Big is smuggling and laundering a pirate gold hoard to finance SMERSH operations. In the film he's just a drug kingpin. The book's Mr Big is Buonaparte Ignace Gallia, who uses voodoo and the persona of Baron Samedi to scare people. In the film, Baron Samedi is a separate character who actually seems to be supernatural, while Mr Big is an alter-ego disguise for true villain Kananga. Tee-Hee doesn't have a metal arm in the novel, and Mr Big is killed when Bond blows up his yacht: he survives the explosion but gets eaten by barracuda in the water afterwards.

Unused bits of the book found their way into further Bond movies. Bond and ladyfriend being dragged behind a boat over coral ended up in For Your Eyes Only, while both Felix Leiter's near-death-by-shark ("he disagreed with something that ate him") and the warehouse shoot-out were recycled for Licence To Kill.

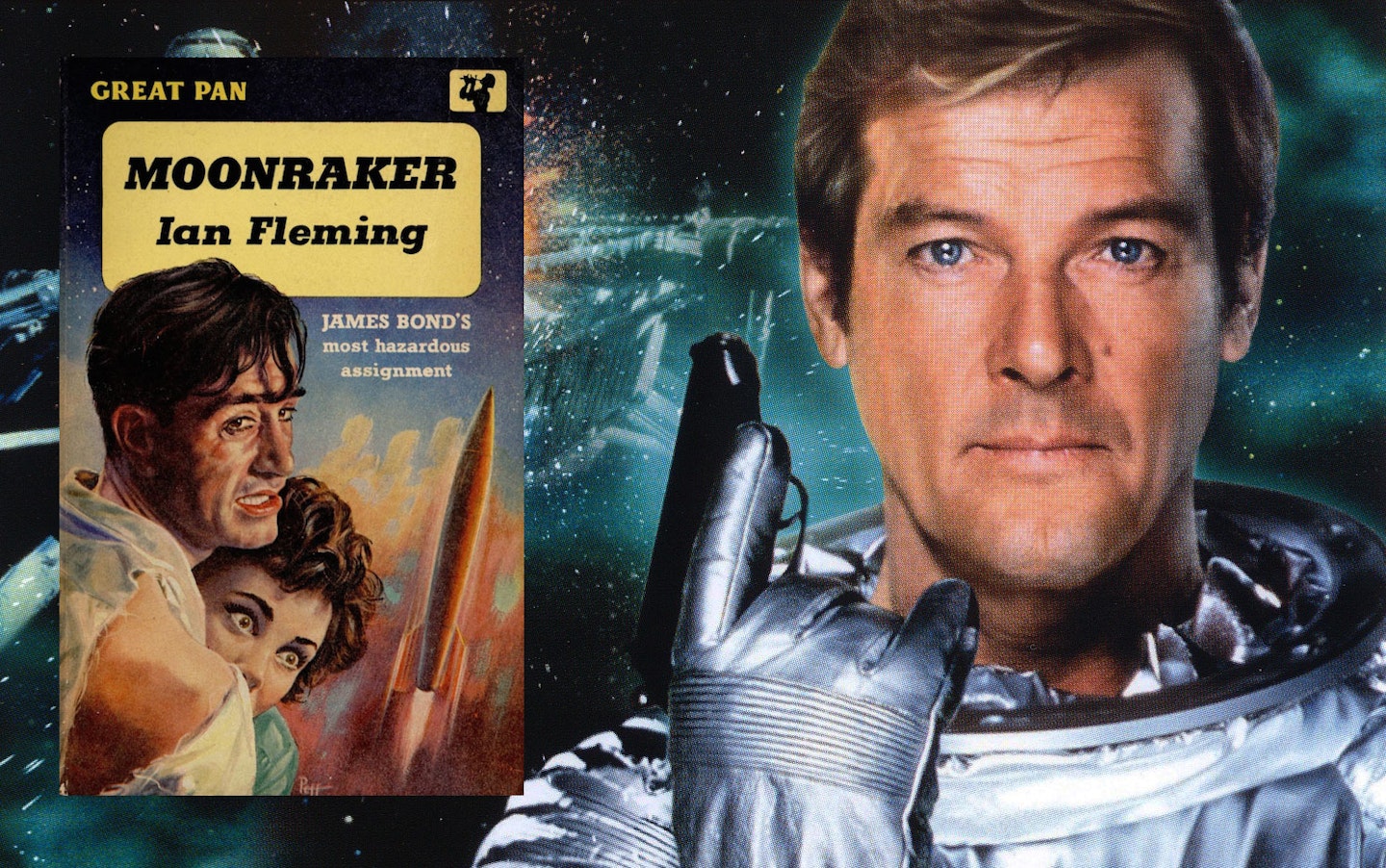

Moonraker (1955)

Filmed in 1979

Almost nothing from the third Fleming novel makes its way into the tenth Bond film - or any of the others to date. Only the name Hugo Drax survives, and the urbane Michael Lonsdale isn't really the same character as the book's red-haired, buck-toothed monster. The film's about the Moonraker space shuttle and a megalomaniac trying to start a new world order in space. The book's about the Moonraker missile programme and vengeful ex-Nazi Drax's attempt to turn it against the UK. Drax's henchman in the book is the despicable Krebs, whereas in the film it's Jaws: back by popular demand from The Spy Who Loved Me. In the book, Drax has a team of scientists whom he makes shave their heads and grow big moustaches. There's also a great car chase from London to Deal and another really long card game. And the "Bond girl" is Gala Brand, not Holly Goodhead.

M's club, Blades, where Drax is first encountered cheating at cards, finally appeared onscreen in Die Another Day. Rosamund Pike has said that her character in that film, Miranda Frost, was originally called Gala Brand in the screenplay.

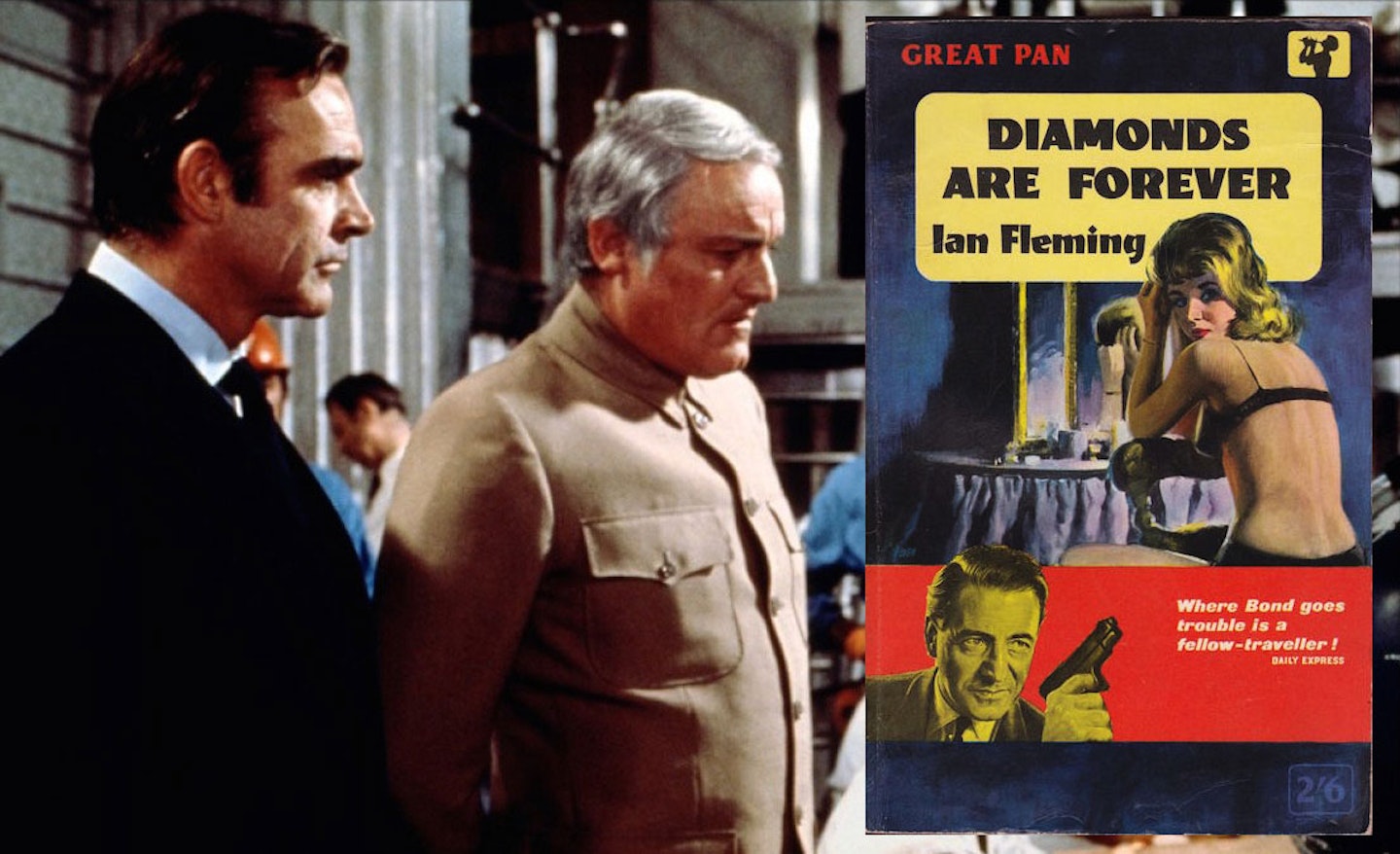

Diamonds Are Forever (1956)

Filmed in 1971

Nothing to do with Blofeld, or diamond-powered death-ray satellites, or moon buggy chases... Fleming's Diamonds Are Forever is a pretty straight gangster thriller in which Bond takes on The Spangled Mob (who reappear in Fleming's Goldfinger and The Man With The Golden Gun). The film plays that aspect essentially as a weird comedy, and bolts it onto a typically outlandish Blofeld world-domination plot. The book does give the film a few characters, like Shady Tree, Tiffany Case, and henchmen Mr Wint and Mr Kidd. Some of it does take places in Las Vegas too, and you could just about argue that the film's early sequence with the Blofelds being cloned out of mud pits is kind of drawn from the novel's chapter in the mud baths. Just about...

From Russia With Love (1957)

Filmed in 1963

The second Bond film is a pretty faithful adaptation of the fifth novel (one of John F. Kennedy’s favourite books, trivia fans). What we don’t get in the movie version is the lengthy preamble about Grant, revealing, among other things, that he reacts to the full moon. The film also, as ever, replaces SMERSH with SPECTRE, and has Grant keep popping up to, peculiarly, save Bond’s life. But otherwise it’s pretty much plain sailing aside from minor cosmetic differences: the train sequence, the gypsy camp scene, the blades in Rosa Klebb’s shoes and even the contents of Bond’s Q-Branch briefcase all come from Fleming. The film changes a couple of locations, adds that pre-credits training sequence, and throws in a spectacular boat chase. The book ends on a cliffhanger where Bond might be dead. The film doesn’t (although you could say it sort of does that at the beginning).

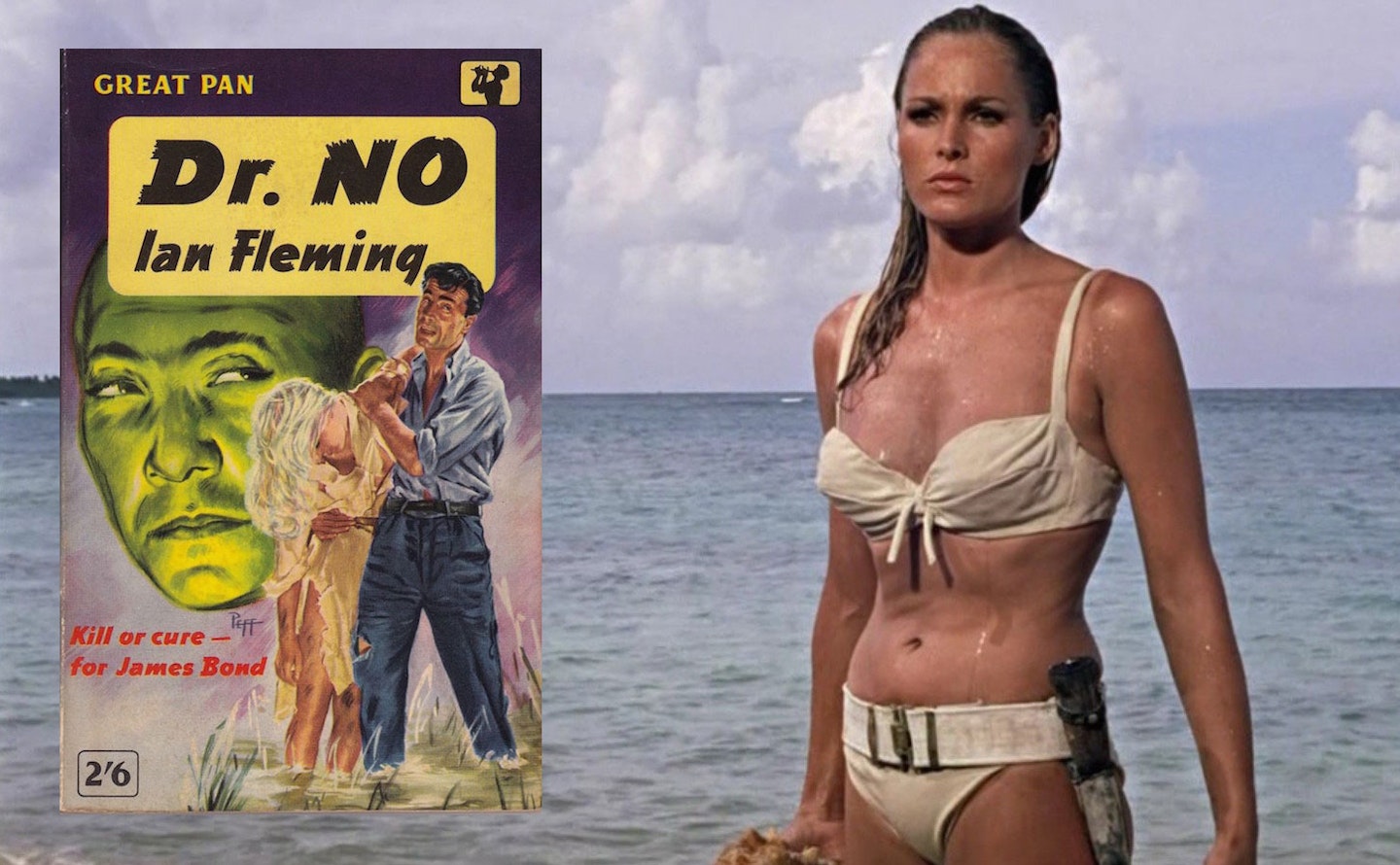

Dr. No (1958)

Filmed in 1962

Book six, film one – and like From Russia With Love, they match reasonably closely. Bond heads to Jamaica to investigate the death of Strangways, unpicks the mystery of Crab Key and its “dragon”, meets Honey Rider (actually "Honeychile") and defeats the dastardly Doctor. In the book, No is a medical doctor trying to steal American missile technology. In the film, he’s a nuclear physicist and his plot is appropriately atomic. In the film, No dies by sliding down a ladder into an irradiated pool in his exploding facility. In the book, he’s buried alive /smothered to death in a mountain of bird guano. The film adds Professor Dent, but sadly (or perhaps sensibly) omits the lengthy sequence where Bond undergoes Dr. No’s obstacle course and fights a giant squid. The spider that menaces Bond in the film is a centipede in the novel. Oh, and a word about Quarrel. In the book, this is the same Quarrel that Bond previously teamed up with in Live And Let Die. In the films, which happen in the opposite order, Crab Key is Bond’s first meeting with Quarrel, and the guy Roger Moore meets a decade later is Quarrel Jr.

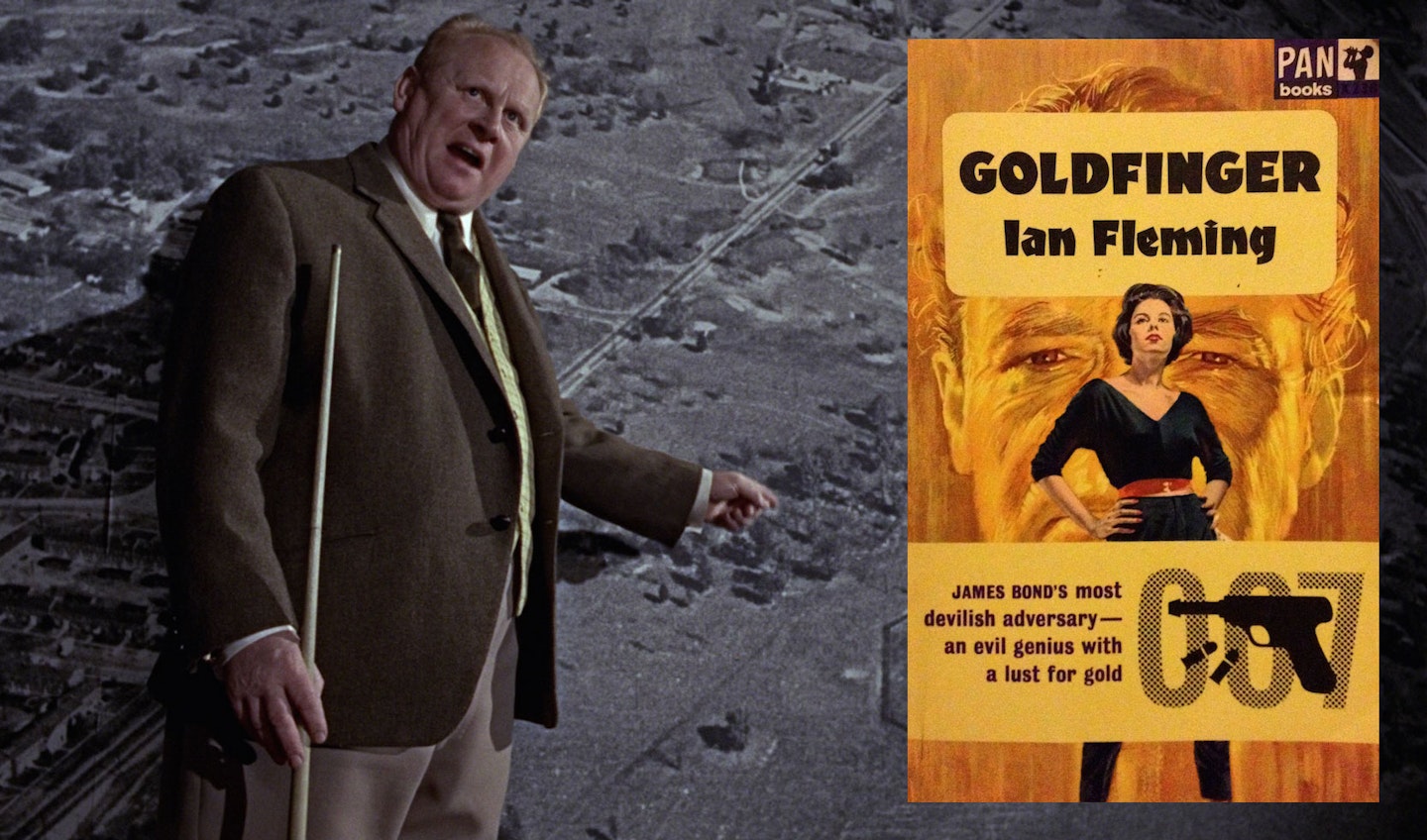

Goldfinger (1959)

Filmed in 1964

Novel number seven, but still early days for the film franchise. The third movie hews very closely to the book: the characters, Bond’s first meeting with Goldfinger where he exposes him cheating at cards, the golf match, the Switzerland drive, and even the cars – Bond’s Aston Martin DB5 and Goldfinger’s Rolls Royce Silver Ghost – all come from Fleming. The major wrinkle is that, in Fleming’s plot, Goldfinger wants to rob Fort Knox. In the film his scheme is to irradiate all the gold there with a dirty bomb. Jill and Tilly (Masterson in the film, Masterton in the book) die earlier, although Jill’s smothering in gold is Fleming’s device. The laser that Goldfinger menaces Bond with in the film is a circular saw in the novel. And in the book it’s Oddjob that gets sucked out of the window of the plane: Goldfinger just gets throttled to death by a frenzied 007. And the extraordinary Q-Branch "modifications" to the Aston Martin are, of course, film only.

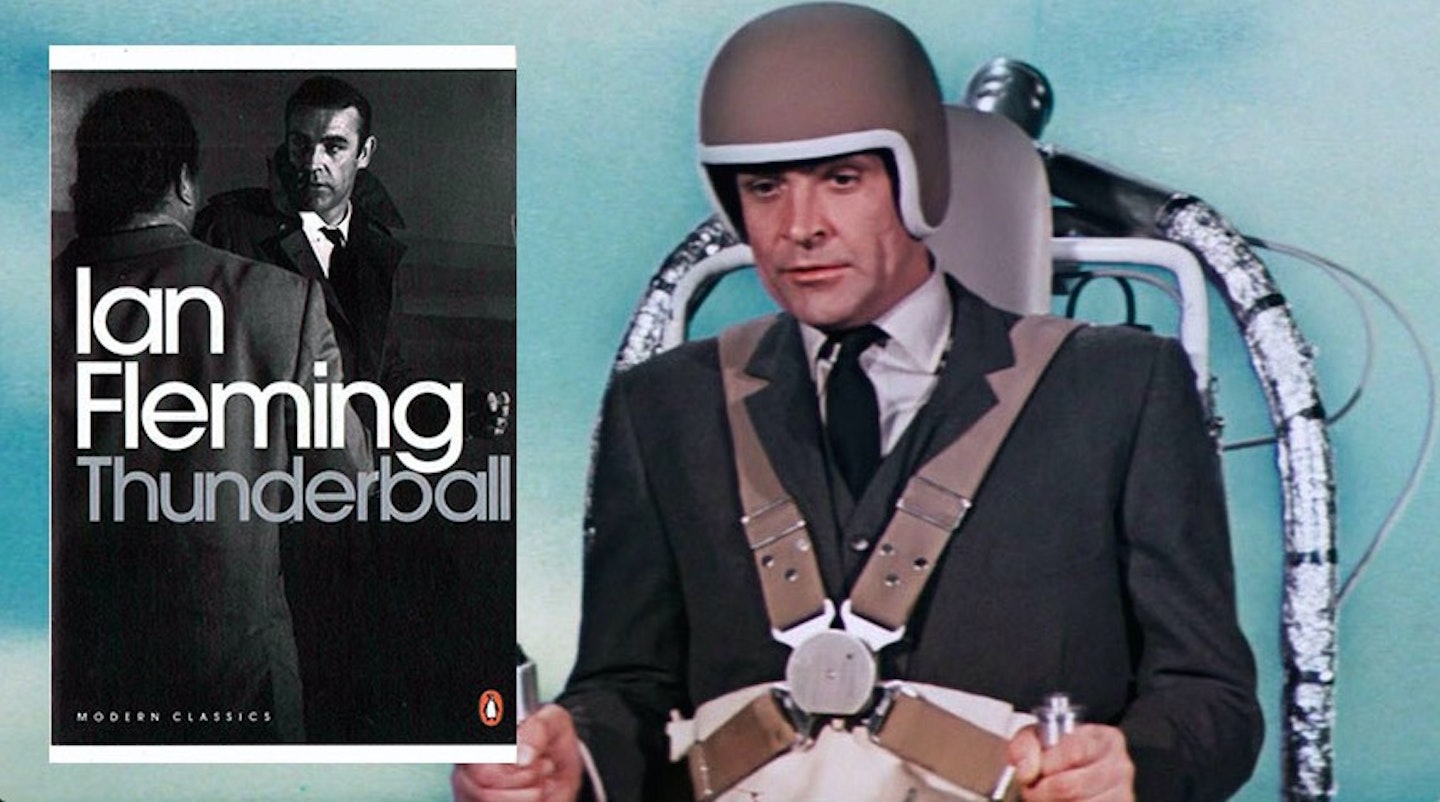

Thunderball (1961)

Filmed in 1965

As has been much documented elsewhere, Thunderball was originally supposed to be the first Bond film, with Fleming working up an original screenplay with producer Kevin McClory. When that film fell through, Fleming turned it into the eighth of his Bond novels – and cue lawsuits, copyright claims, Never Say Never Again and so on. As such, Thunderball, uniquely in the book series, is a novelisation of an at-the-time unmade film. And as such, when the film happened, it was understandably extremely faithful to its source: Bond is sent to a health farm where he’s targeted by SPECTRE-man Count Lippe; Bond plays cards with Largo; SPECTRE has hijacked a plane full of nuclear missiles and stowed them underwater in the Bahamas; Domino is the girl; Largo’s boat is the Disco Volante... and so on. If the details in the film aren’t always identical to the book, they’re at least extremely similar. The only major deviation is Bond’s fake funeral and the nonsense with the jetpack in the pre-credits sequence.

The Spy Who Loved Me (1962)

Filmed in 1977

An aberration in the novel sequence, this one isn’t really about Bond at all: it focuses on holidaying journalist and former finishing-school girl Vivienne Michelle, who rocks up at a dodgy empty Canadian motel off-season to be terrorised by gangsters Horror and Slugsy, who’ve been employed to burn the place down for the insurance. Bond only shows up to save the day in the novel’s final third. It sees Fleming writing in the first-person as a woman: something that was hilariously far beyond his capabilities (hearing Rosamund Pike straight-facedly intone the assertion "all women love semi-rape" for the audiobook is a proper choke-on-your-coffee moment). Fleming forbade that this one be turned into a film at all, hence the Roger Moore classic has nothing to do with it beyond the title. Horror has steel caps on his teeth, so he clearly had some bearing on the film’s Jaws, but that's about it.

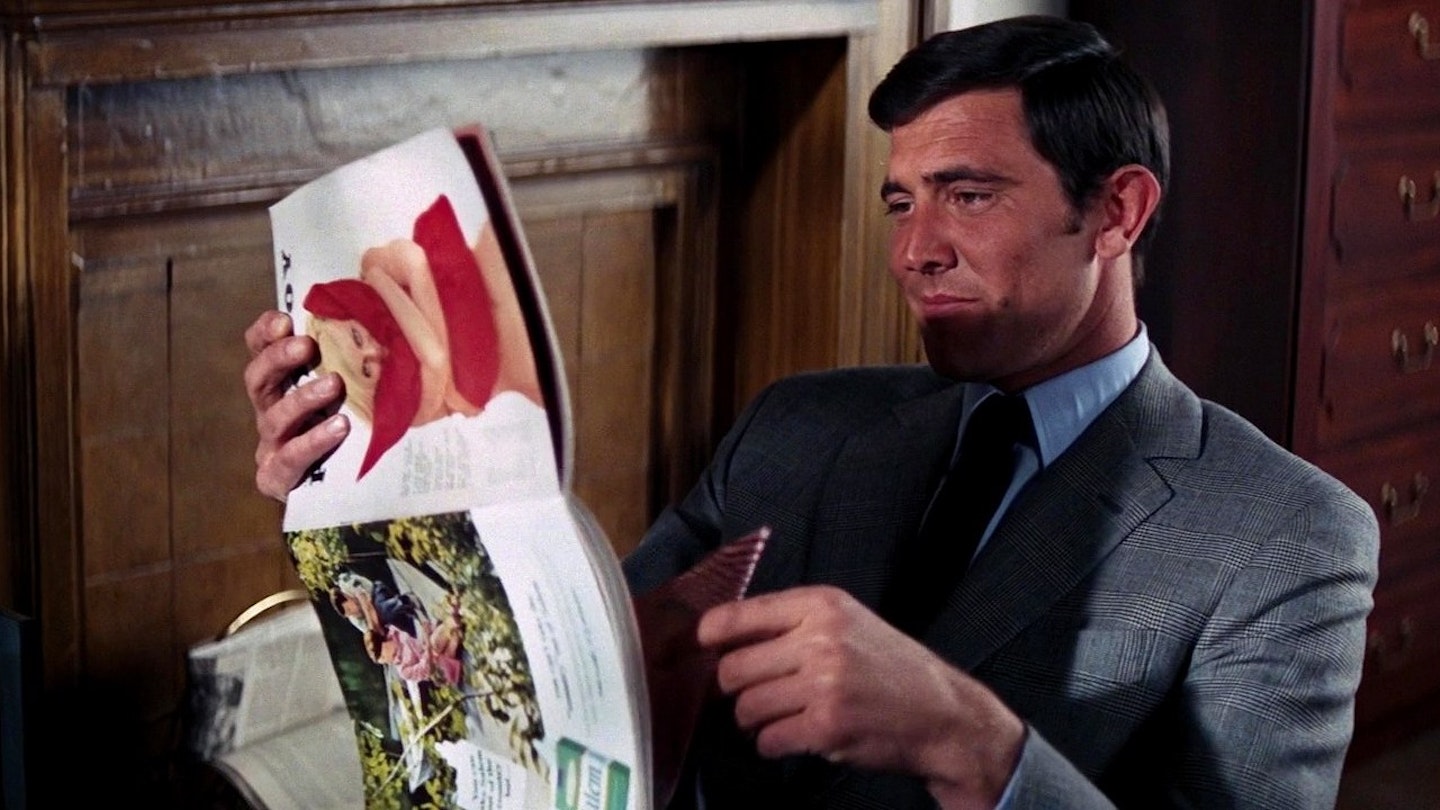

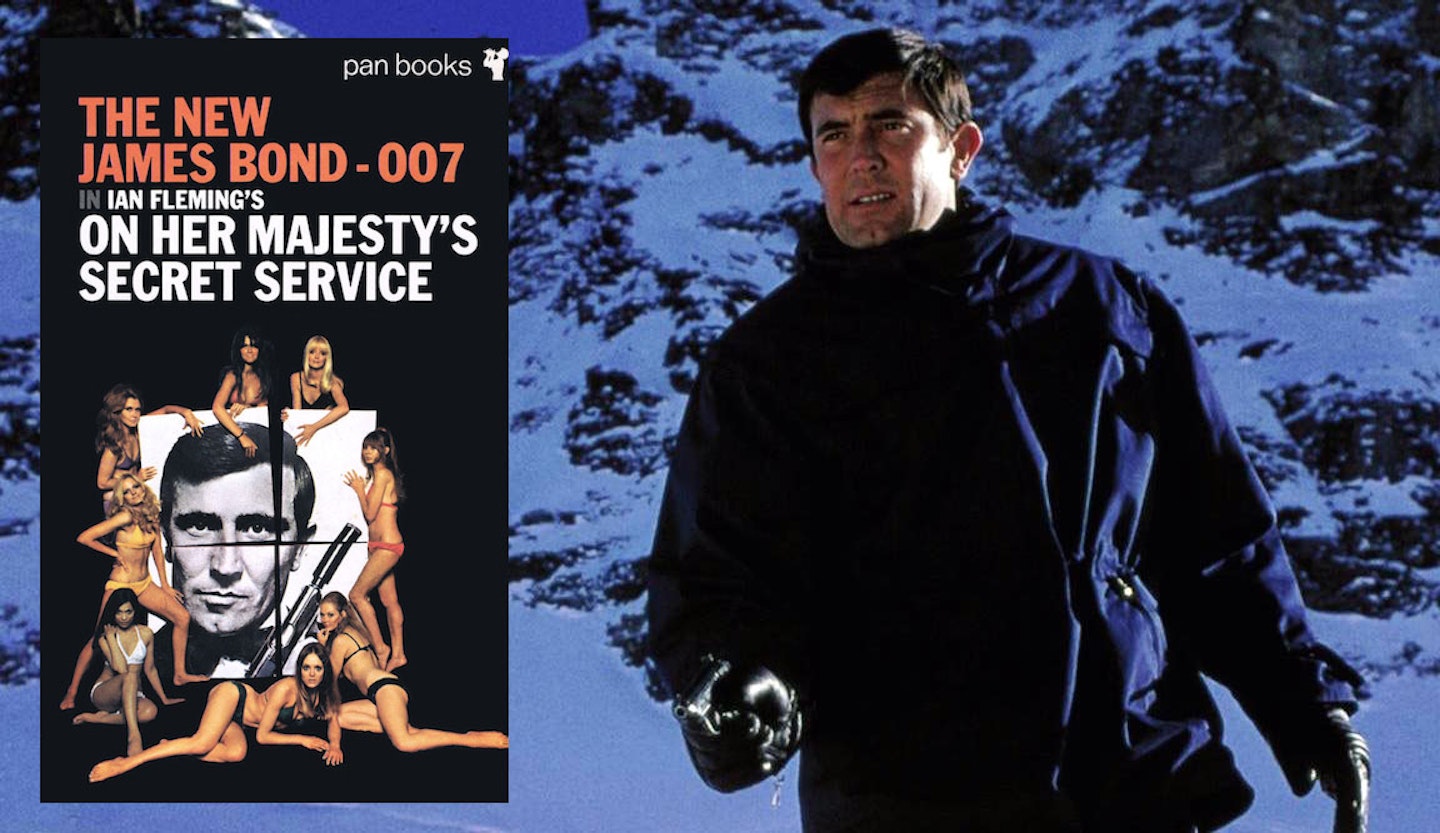

On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1963)

Filmed in 1969

Arriving after the off-message volcano-based fireworks of You Only Live Twice, the film of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service is a back-to-basics affair that sticks closely to its source novel. The characters, the plot, the heraldry and the set pieces see only minor cosmetic deviations in the adaptation. In the book, Bond is getting fed up chasing Blofeld and considers resigning from the Service. In the film he considers resigning because M threatens to take him off the Blofeld case. In the book, Tracy’s attempted suicide on the beach happens after Bond has met her at the Casino. In the film it’s the other way round – but it makes little difference, aside from Bond in the film being kidnapped alone, while in the book he’s still with Tracy. The sequence with the inconvenient other agent who almost blows Bond’s cover plays out slightly differently in book and film. But Fleming’s incredibly downbeat ending, famously, is retained on screen, right down to the line "We have all the time in the world".

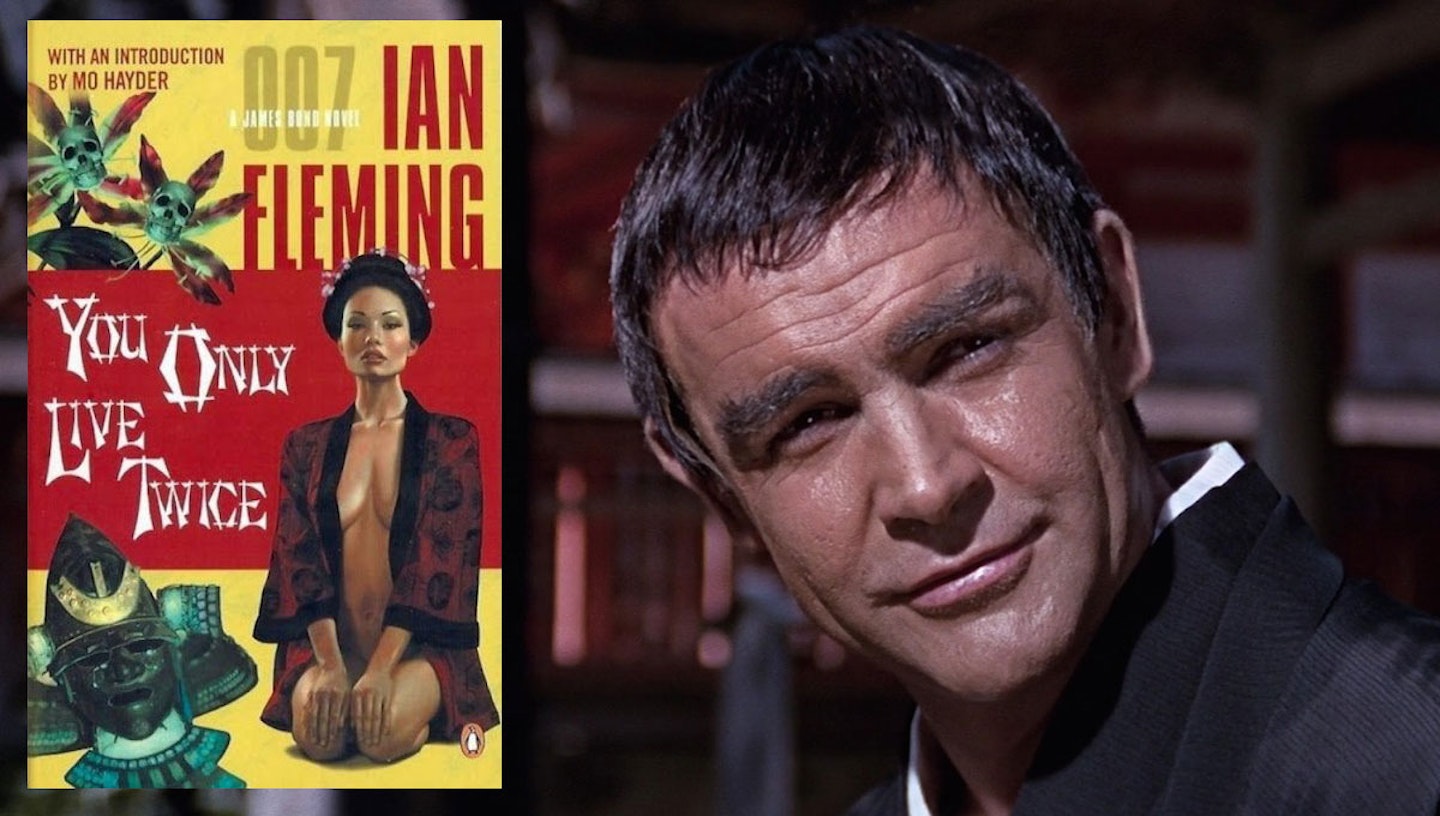

You Only Live Twice (1964)

Filmed in 1967

You Only Live Twice was Fleming’s immediate follow-up to OHMSS, whereas on film they happen in the reverse chronology. So in the novel, Bond is completely driven by his desire to get revenge on Blofeld for the death of Tracy, whereas in the film he hasn’t even met Tracy yet. Ditto, sort of, Blofeld’s henchwoman Irma Bunt, who returns in the novel but hasn’t arrived yet in the film. Book and film share the Japanese setting and most characters, but in the film – which starts in space! - Blofeld is operating from a volcano base and plotting to start a nuclear war between the US and the USSR at the behest of the Chinese, whereas in the novel he’s posing as Dr. Shatterhand and running an odd castle garden facility where suicidal Japanese can book a creative way to kill themselves. In the book, Blofeld is finally defeated and, like Goldfinger, is simply strangled by Bond. In the film Blofeld lives to die another day (and another). And the film has one of those scenes where Bond and his girl get it on in a life raft as they’re rescued. In the novel, Bond narrowly escapes the Shatterhand estate and is rendered an amnesiac. Presumed dead by the Service, we leave him living a simple life in a fishing village with Kissy Suzuki, only gradually beginning to come back to himself in the story’s final lines. Fleming includes Bond's obituary, written by M, as happens in Skyfall

The Man With The Golden Gun (1965)

Filmed in 1974

Fleming’s final novel – published posthumously – sees Bond, still suffering the after-effects of You Only Live Twice, brainwashed by the Russians into attempting to kill M. Once back in the hands of the service he’s deprogrammed and given the chance to regain his double-0 status with the impossible mission of assassinating crackshot gangster Francisco Scaramanga. Scaramanga is involved in a corrupt hotel development in Jamaica in cahoots with an organised crime conglomerate and the KGB. He’s also in on a plot to destabilise Western interests in the Caribbean sugar industry and inflate the value of the Cuban sugar crop, along with some stuff about trafficking prostitutes, running drugs and setting up dodgy casinos. He has his fingers in a lot of pies, does Scaramanga. Bond kills everyone, including Scaramanga, who he chases into a swamp and shoots.

None of this is in the film – although the kidnap-and-brainwashing has vague echoes in Die Another Day (Bond emerges miraculously unscathed on that occasion). The Golden Gun movie relocates to Scaramanga’s secret island in the Far East and reinvents the villain as essentially Bond’s evil twin. His plot there is about the 70s-topical world energy crisis, and his attempt to get the jump on it with his "Solex Agitator" technology. The film’s Bond girl is Mary Goodnight, who is in the book. The 00-section secretary, reimagined in the film as a crap new field agent, was a regular in Fleming’s later stories – she also shows up in OHMSS and You Only Live Twice, and the short story The Property Of A Lady. This is her only film appearance.

The Short Stories (1959-1966)

Filmed 1981-2015

When the films ran out of novels, they started turning to the shorter works. Fleming wrote nine Bond short stories, originally published in outlets like The Sunday Times, The Daily Express and Playboy. They were first collected as For Your Eyes Only, published in 1960, and Octopussy & The Living Daylights, which came out posthumously in 1966. For the release of Quantum Of Solace in 2008, Penguin collected them in a single volume for the first time, under that title.

From A View To A Kill is about Bond killing a motorcycle dispatch rider, and gives nothing to the film apart from its reworked title (the only Fleming title to be adjusted by the films) and initial setting in Paris.

For Your Eyes Only and Risico were smartly combined for the film For Your Eyes Only: Judy Havelock (renamed Melina for the movie), her bow and arrow, and the death of her parents come from For Your Eyes Only, while Colombo and Kristatos are from Risico. These were mixed in the film with a new Cold War plot about the ATAC machine, as well, as we’ve already said, as the coral-dragging sequence from Live And Let Die. The Identigraph comes from Goldfinger.

Quantum Of Solace is about Bond hearing a depressing after-dinner story of marital strife from the Governor Of Nassau, and gives nothing to the film apart from its title. Although you could argue that the notion of the Quantum Of Solace itself – when that "quantum" drops to zero, you’re capable of inhumane acts you wouldn’t have considered before – feeds into the film’s vengeance-fuelled post-Vesper Bond.

The Hildebrand Rarity is about an American millionaire searching for a rare fish while treating his wife badly. Bond disapproves. The millionaire, Milton Krest, and his boat, the WaveKrest, were folded into the Dalton-era Licence To Kill. The name Hildebrand itself shows up in Spectre, as an MI6 safe house.

The Living Daylights sees Bond tasked with assassinating a sniper in East Berlin, but, on finding said gunman is a moonlighting female cellist, opts merely to scare the living daylights out of her instead. The whole story is faithfully adapted as the very beginning of the film, which then carries on with original material about KGB defectors and battles in Afghanistan.

007 In New York is a very short, throwaway travel piece for the Sunday Times including Bond’s recipe for scrambled eggs. There isn’t really anything in it to adapt, but it did give the name "Solange" to Casino Royale in 2006.

Property Of A Lady involves Bond at Sotheby’s messing up a Russian plan to pay an agent by rigging an auction for a priceless Fabergé trinket. It plays a part in the film Octopussy (where “The Property of a Lady” is the auction's title). In the film the item up for auction is a Fabergé egg, while in the story it’s a globe.

And Octopussy itself gives the film of the same name very little, bar the title and background for the sort-of villainess who inherits the moniker. The story has Bond tracking down Major Dexter Smythe for a war crime. He allows him to commit suicide rather than be arrested, and this is what has happened to Octopussy’s father in the film. The story also gives us Hannes Oberhauser, a father figure (and ski-instructor) to the orphan teenage Bond, who was murdered at the end of WWII by Dexter-Smythe, his body showing up years later frozen in a glacier. So it’s a personal mission for Bond. This thread has made its way into Spectre, where Hannes’ son Franz is played by Christoph Waltz…